Purr is a new programming environment for collaborative programming. In other words, the primary goal of Purr is to support the idea of programs that are built by many people, concurrently. Purr extends the notion of collaboration to computers, so they become active agents in the process of programming, being able to answer questions and offer suggestions.

Why?

Purr takes into account that programming is increasingly done in a distributed way, just like many other human activities. People don’t need to be in the same building to work together anymore. We can use tools like instant messaging, video conferences, and even edit documents together in real-time. The range of ways we can interact with each other and collaborate on a project has grown significantly in the last 70 years.

When you compare programming with other human activities, there are some very particular issues that we shouldn’t ignore. One of them is that most of the collaborative work in programming is done asynchronously, and not coordinated. We develop independent components, and we’re expected to put them together into some working program, and make sure that program continues working despite its components changing under us all the time.

Purr’s primary goal is to make software engineering reasonable under these circumstances. To allow components to be written and evolved independently, but still combined in several different contexts (many of which the original developers didn’t intend for) without issues. To support software that relies on the work of many different people, some of which you may not fully trust with your data. These problems currently lie under the surface of every mainstream programming tool, and sometimes it’s a wonder that things work at all. Particularly with respect to security and privacy.

A secondary goal for Purr is to support the idea of computers as personal assistants. This is not a novel idea; you can see a lot of this in the 60s and 70s. For example, Alan Kay suggested something similar with his Dynabook idea. It also shows up in a lot of end-user places today—Siri and Cortana might the most popular examples—, but not much in programming. Programmers mostly just get the computer to tell them “I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.”, over and over and over again.

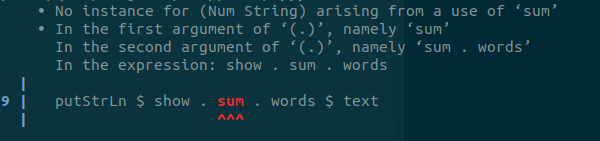

An inscrutable type error message in Haskell

An inscrutable type error message in Haskell

How?

As said before, Purr is a programming environment. In this sense it’s much like RPG Maker or Excel—it gives you all of the tools you need to build and run programs, and some of these tools happen to be programming languages. You never need to use a separate tool, or worry about cross-platform development.

Purr is image-based, in a way similar to Smalltalk environments. This means that instead of storing your programs in text files, Purr stores them in a database. When you edit these programs you’re also manipulating nodes directly in this database, rather than text. If you’re familiar with projectional editors, like Jetbrain’s MPS, the experience should feel similar. As a result, Purr can store much more information about intentional changes, can be smarter about version merges, and doesn’t have to deal with things like syntax errors.

The Purr environment supports live and literate programming as a core part of its programming workflow. People are encouraged to document their programs using tools similar to Bret Victor’s Explorable Explanations. The concept of lenses allows programs to be visualised in multiple ways, and users to extend the catalogue of visualisations by writing their own. This is similar to what Glamorous Toolkit offers in the Smalltalk community.

To support all of this Purr has a computational model based on ideas from Functional Programming and Object-Oriented Programming, as well as some inspiration from less well-known paradigms. Things like actors, algebraic data types, pattern matching, and higher-order programming are certainly a big part of it, but Purr also includes less popular ideas like contracts, algebraic effect handlers, and capability security.